In a world where almost everything can be streamed, simulated, or scrolled through, Albert Almeida, consultant to the chairperson’s office, and head - marketing and PR, National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Mumbai, is aiming to build something stubbornly physical: rooms full of people, sitting together, paying attention to the same thing at the same time. His work is less about distribution and more about presence.

That focus feels timely.

After years of screen fatigue, people aren’t just scrolling less; they’re choosing to show up elsewhere. Social media growth has slowed to low single digits globally, while live and in-person experiences are among the fastest-growing segments in culture and entertainment. What’s driving that shift isn’t just exhaustion, but disillusionment.

Gartner predicted that in 2025, 50% consumers would abandon social media or sharply limit their use. Furthermore, GWI data for the Financial Times revealed that adults have reduced their social media time by nearly 10% since 2022, primarily driven by younger users who once fueled growth. Teens and people in their twenties are moving away from active posting towards passive browsing or spending more time offline altogether.

It’s not just saturation. It’s a change in how people relate to platforms. And it creates space for theatre and live performance, not as content alternatives, but as answers to a growing desire for presence, attention, and shared experience.

For Almeida, theatre, music, and live performance aren’t nostalgia projects - they are social infrastructure, how trust is rebuilt after rupture, how culture survives beyond algorithms, and how institutions stay meaningful across generations. At NCPA, his job isn’t about selling tickets or attracting sponsors - it’s to hold together a fragile ecosystem of artists, audiences, patrons, brands, and traditions, without flattening any of it into transactions.

His own path there was unplanned. When the pandemic shut live entertainment down, everything collapsed at once, including his relationship with BookMyShow. NCPA was a client, and its chairperson knew Almeida was in transition. He asked if Almeida could help for a while. Almeida wasn’t looking for another role. He just wanted to offer his time and whatever experience he’d gathered.

One meeting became another. He kept coming back. Eventually, the chairperson insisted that he be paid. Somewhere in that slow drift from helping out to showing up every day, he realised he was in.

What followed was a patient rebuilding.

Manifest caught up with Almeida to understand how live performance became a form of social rebuilding after Covid, why the arts can’t be treated like mainstream media content, and what it takes to sustain a cultural institution without hollowing it out.

Edited excerpts:

How did you strategise the live space and get people back after the pandemic?

All live spaces were hit hard, but indoor venues like ours faced a unique challenge. During the lockdown, every message was about avoiding closed spaces and maintaining social distance. So the sentiment was almost anti-theatre, anti-gathering. We were genuinely worried about our business during that time.

Then, through a bit of luck, call it providence, I had a chance meeting with Ashwini Bhide from the BMC. We were talking about doing something in the park, which aligned with what NCPA wanted to do. She said we were welcome to, and even offered to come and officially announce that it was safe to gather again.

So we launched NCPA at the Park at Cooperage. The chairperson attended, we had a great turnout, and the Symphony Orchestra of India performed. People were starving for live experiences again.

That moment changed everything. Four years later, we’ve completed five seasons. It’s not just a property that worked; it’s grown stronger every year.

How do you approach sponsorships without compromising the institution?

The first thing I realised was that NCPA isn’t a commercial entity. It’s a non-profit. Its DNA is different. Sponsorship isn’t instinctive here. The culture is about covering costs at best.

We’re not set up to chase commercial success. We exist to preserve, present, and propagate the finest performing arts. At the same time, we have to run sustainably. So the mix always includes commercially viable shows and others that may never attract sponsorship but are central to our mission.

A lot of our work is invisible. People see the performances, but they don’t see the training, the nurturing, the lineage-building.

Indian classical music, for instance, survives through oral tradition, the guru-shishya parampara (guru-disciple tradition). There isn’t a formalised institutional structure, the way there is in the West. So institutions like ours have a responsibility to sustain that lineage.

We bring in masters like tabla player and composer, Zakir Hussain, not just to perform, but to teach, to inspire, to pass knowledge forward. We’re grooming the next generation so the art doesn’t die when one great artist is gone.

That’s why support matters. And it’s karmic. When the work is honest, people recognise it.

Citi is a great example. This year marks 15 years of Aadi Anant, our festival centred on the guru-shishya (teacher-student) tradition and artistic innovation. That journey exists because of Citi’s support. We can point to tangible outcomes: hundreds of students trained, dozens of teachers supported, thousands of people exposed to these forms. That becomes proof.

And others follow HSBC, Bank of America, JSW, and Jefferies. We sustain ourselves through three streams: CSR, foundations, and sponsorship. CSR is one part. Foundations are another, especially family trusts that reinvest corporate success into social good, including the arts. Sponsorship is the hardest. We don’t want to reduce the arts to an Excel sheet. But when done right, it works. Audiences say, ‘If it wasn’t for Citi, we wouldn’t have experienced this orchestra.’ That builds brand love, not just recall. When people choose between two banks, values start to matter.

How do you attract younger audiences?

There’s a perception that NCPA isn’t for young people or that it’s only for South Bombay (Mumbai). That’s on us.

We present a lot of regional content, Marathi, Gujarati, Hindi theatre, Indian music and dance, and English programming is actually much smaller in comparison. But people don’t see that.

We have introduced informal formats, picnics at the park, meet-the-author sessions, youth bands performing to small crowds, improv, and stand-up comedy.

We’re building new days in the week where young people come to laugh, hang out, and experience culture in a casual way. Even the Symphony Orchestra seasons now attract young audiences. There’s a moment in a person’s life where they want to feel special, to experience something formal and meaningful. It’s not the same as a casual night out, and young people get that.

How does social media fit into this?

Social media isn’t a ticketing platform. It’s a conversation space.

After the pandemic, I brought in younger talent to handle. We’re learning constantly. It’s not just about 'Buy tickets.' It’s about making people want to belong.

Our following has grown, our content has evolved, and we’re on the right track. The challenge is volume. We have five genres, plus a revived gallery, plus F&B partners who want representation. There’s a lot to talk about without overwhelming audiences. There’s constant debate about whether to split handles or consolidate. We’re figuring it out as we go.

What marketing trends have worked this year in 2025, and which were roadblocks?

Scale was the challenge. A sponsor would say: We need to reach a thousand people in the hall. So we built digital layers around that, social, YouTube, amplification, and partners like BookMyShow. Now we offer both reach and depth. But authenticity is non-negotiable. The moment marketing feels forced, people pull back. Same with influencers. Relevance matters more than reach.

Do third-party ticketing partners work or in-house?

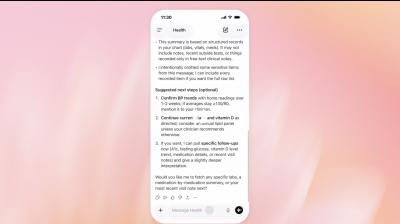

On ticketing, both our platform and partners work. BookMyShow, for example, earns its commission, and I don’t hesitate to pay it. They bring value. We can improve our own systems with better CRM, real-time intelligence on buying patterns, and eventually a stronger website. It’s not about building walls, it’s about collaboration. This can’t be done by a small team alone. It needs partners, and it needs journalists who understand why the arts matter.

People overlook the importance of arts and culture because they don’t live in that world. But art is one of the few things that unite people beyond identity. Think about music: when someone says “I love jazz,” they aren’t Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, they’re just jazz lovers. Same with cricket. When two communities were set against each other, they played cricket together, and suddenly the labels dropped.

Talk to anyone at the top of their field: doctors, lawyers, CEOs, and many will tell you their passion is music, dance, or books. It gives them a space to think, reset, expand their mind, and let go of bias. That’s why companies like Bloomberg and Bank of America run internal arts programs. They believe the arts elevate conversation and build better managers. It’s good for business, and good for who you are as a person.

Do you see tangible brand success?

It’s hard to draw clean lines between sponsorship and direct outcomes. What I do know is that when brands partner with us in the right way, they come back happy, and they come back again.

Our upcoming Zakir Hussain tribute is a two-day festival. We reached out to a few likely partners, and two of our three sponsors are regular supporters. Axis Bank, for instance, didn’t hesitate because its earlier associations, like with Zubin Mehta, worked well. Bringing Axis Bank's Burgundy Club members to an NCPA evening is an easy yes; people leave feeling it was a great experience, and they want more. If I can deliver that consistently, it’s a win for them.

JSW is another example. They want to be associated with the arts and with meaningful work. That intent is led at the top and flows through the group. The value isn’t just access or invitations; it’s that the people they bring see the company giving back.

The same is true for partners like Citi, Bank of America, and HSBC. They keep growing their association because they feel their support is well used. The only real limits are conflicts; if a category is already taken, I can’t bring in another. That’s where the constraints come in.