Most corporate stories are written after the dust settles, when balance sheets appear healthy again, and memories have softened the sharp edges. The recently launched book The Rollercoaster of Hope does the opposite. It steps into the mess and stays there, capturing what it feels like to run a public company when revenue disappears, lenders grow restless, and every decision carries the weight of survival.

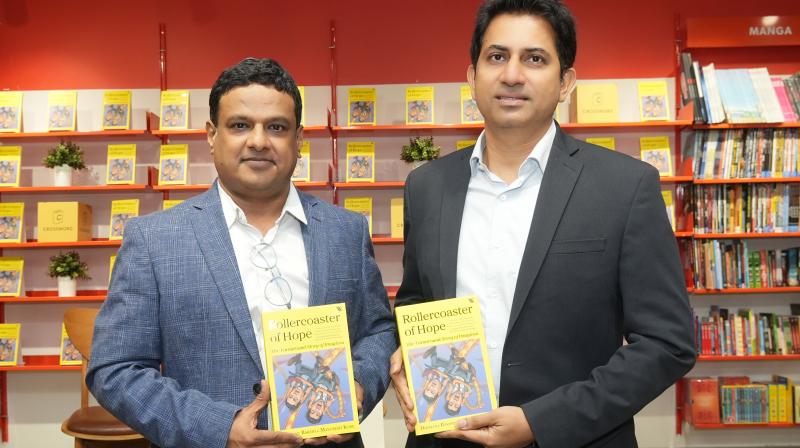

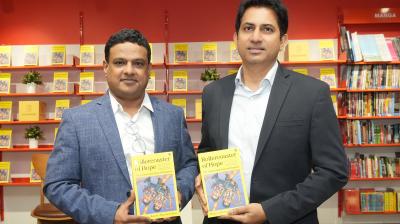

Over two and a half years, Imagicaaworld Entertainment’s CEO, Dhimant Bakshi, and CFO, Mayuresh Kore, aimed to document their fight to keep the theme park alive through the pandemic, the NCLT process, and a financial crisis that threatened everything the brand had built.

The book aims to deliver a ground-level view of leadership under siege, where optimism must be manufactured daily, and trust becomes the only real currency.

What makes the narrative land is its refusal to polish the truth.

At its heart are uncomfortable questions: What do leaders do when money dries up? How do you keep people believing without clear answers? And how much honesty can a listed company afford when survival is on the line?

We caught up with Bakshi and Kore to discuss why they told such a vulnerable story, how they balanced disclosure with responsibility, the marketing behind the book, and what hope means when an entire organisation hangs in the balance.

“The main purpose of writing the book was that so many of these stories play out inside the corporate world, but they rarely get spoken about honestly,” revealed Bakshi.

“We are a publicly listed company, and companies like ours usually follow a standard way of operating, a set method to solve problems. But when a business faces unfamiliar challenges, how does one effectively deal with them? Then something like Covid happens, a global shock no one was prepared for. We wanted the book to capture those experiences and case studies so people could see how hope can become a lever, even a tailwind, for survival.”

Bakshi added, “There are also people you meet who try to profit from your vulnerabilities, and we wanted to talk about how important it is to stay alert to that. We talk about how one manages and builds a team’s morale, how one works with collective wisdom, and how one partners with others when everything feels uncertain. And finally, the most basic question: when cash dries up, and one is running a company, what can one do?”

Bakshi shared that the intent was never to produce a motivational memoir.

He said, “We wanted the book to be unvarnished, unfiltered, straight from the gut. To tell the world that situations can change, that you don’t have to feel trapped. If even one person somewhere benefits from what we’ve shared, we’ll consider it worthwhile.”

The timing of launching the book, Bakshi admitted, was dictated by life rather than strategy. He expressed, “We were writing this while still doing our day jobs, so time was always the challenge. It took almost two and a half years to publish. Once we were somewhat out of the woods, both of us felt it was time to put it out for people to read.”

Being a listed company added its own complications. “We have followed every requirement on the governance side,” Bakshi explained. “Even during the most critical phases, we never crossed the line. What appears in the book is only about 50 to 60% of everything that happened. We had to choose the stories that were the most meaningful.”

Kore believes the book speaks beyond crisis.

“If one zooms out, every function in a company has multiple stakeholders,” Kore expressed. “In a crisis, this gets amplified because interests are not aligned. A banker wants recovery, employees want salaries, suppliers want payments, promoters want to retain the company, and investors want upside. In our case, there were also local communities, regulators, and the government. Balancing all this without cash flow was the real test.”

The marketing of the book followed a similarly practical route. Bakshi voiced, “The publishers guided us, our PR agency helped, and we used LinkedIn and Facebook. Through industry connections, we reached people like Anand Mahindra, chairperson, Mahindra and Mahindra, and Nadir Godrej, managing director, Godrej Industries. The first print has already been exhausted, and we are into a reprint.”

Kore added that the brand’s own history created curiosity.

“Imagicaa was known to be in trouble for years. When the change of management happened, people wanted to know what really went on behind it. Bankers, lawyers, and students are looking at this as a case study," Kore stated.

Rebuilding after Covid

The conversation then shifted to how the company rebuilt demand after the pandemic.

Bakshi explained, “We are a high standard deviation category with lean and peak seasons. We divide marketing into ATL, digital, BTL, and social. Heavy campaigns come in peak seasons through transit media. Influencer tie-ups have become a strong lever.”

Kore noted a mindset shift. He remarked, “Post management change, efficiencies increased because bandwidth was no longer consumed by debt stress. Covid forced us to look through our structure. Imagicaa is a premium product, so it cannot be discount-driven.”

Looking ahead to FY27, Bakshi sounds optimistic. He shared, “We have added new attractions in the theme park and slides in the water park. Offering is complete now, and we are treating this as a combined year for amplification.”

Bakshi repeatedly stated the importance of culture as the real turning point. “No individual is bigger than the team. We were transparent. We told people there will be uncertainty, but they must know what is happening. We opened our doors to ideas. The CEO and CFO don’t know everything. Whoever wanted to leave because of financial challenges was free to do so. There was no stigma," Bakshi shared.

Even in the darkest phase, guest experience remained sacred. Bakshi added, “The frontline team was told only what was needed. Despite everything, we were in the business of happiness."

On what differentiates Imagicaa, Bakshi is clear. He said, “Every attraction was benchmarked to international standards. Equipment is imported from the US, Switzerland, Italy, and the Netherlands. That creates a huge entry barrier.”

Kore credits the ecosystem.

“From day one, we built fine dining, high-quality F&B, and merchandise. Within a day of unlocking, we were ready to open. That showed our ability to deliver despite tough times," Kore explained.

Do Indians still hesitate about leisure? Bakshi believes the curve is turning. He expressed, “There are green shoots, but sustained marketing and safety communication are key. You can’t get customers just like that.”

Both founders return to the central theme of the book. “Our objective was a win-win wheel for all stakeholders,” Bakshi said. “Lenders should get recovery, employee continuity, and guests' value.”

Kore sums up the motivation. “Our book sounds like fiction, but it is non-fiction. We were clear we wouldn’t self-publish unless it had merit. Indian case studies are rare, and we keep borrowing from the West. Everybody has stories. When they come into the public space, they help others move forward.”

And that, perhaps, is what The Rollercoaster of Hope finally offers: not a neat success tale, but a lived map of how a company learned to breathe while underwater, and how two leaders discovered that hope, in business, is less a feeling and more a daily discipline.

.jpg)